Somewhere along the way in writing Alabaster, I had to admit: the goats were running the asylum.

The play began in April 2016—four years before its world premiere—as a two-hander. Clean. Focused. Human. It later won the Calicchio Prize in that same form. At the time, there were two women and a couple of goats, but the goats had no backstory. They were just there—lurking, interrupting, begging for treats at June’s window.

But one of the goats asserted herself around revision #3, after a handful of private and public readings/workshops. This was not the most comfortable time for me to be adding characters; also…the play was clearly already working.

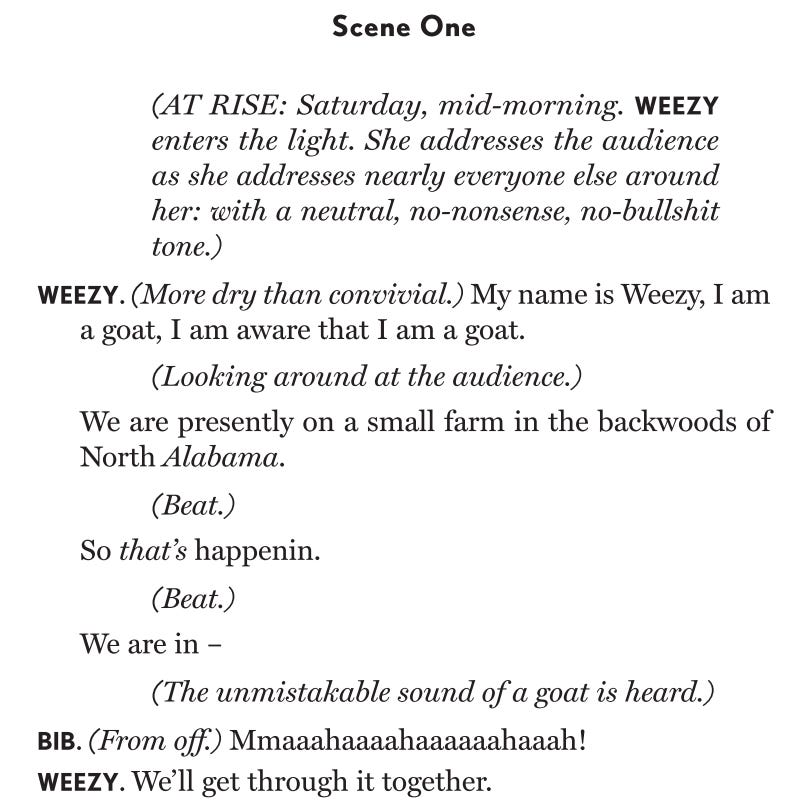

But there was this one particular goat named Weezy. And, man, she would not shut up. “Hey… hey, playwright lady. I have something to say.”

And reader, I really did tell her, “Weezy. Sit down. You’re going to be played by a puppet.”

But she kept nagging at me. Like that restless feeling when you think you’ve left the stove on. You can’t sleep until you’re sure. It was like that.

So, against my better judgment, I asked for a third actor ahead of a reading at Signature. That’s not nothing. When budgets are involved, you need permission, and I couldn’t move forward until I had the green light. Once I got it, I wrote a single scene between her and June. Brought it in as a separate document. A “what if.”

Eight people sat down in the Shen Rehearsal Room on the 4th floor of Signature Theatre in Shirlington, Virginia. I took a deep breath. And we read it.

The response in the room was immediate. “Who is this goat?! We need more of her!” Our reading was the following night and we had one more rehearsal to try things out, so I went across the street to my hotel room and wrote furiously all night long. And just like hot sauce, I put that shit on everything! I gave Weezy narration. Insight. Mischief. Heart. A back story. Suddenly, she wasn’t just a side character—she was the voice of the play. Not a gimmick. No longer a puppet. We read it the following night in front of a packed house and the character of Weezy was all people could talk about.

Hear me: no one writes a talking goat worse than a person who is set on trying to.

There are just some things in playwriting you have to come at sideways.

It’s about recognizing the room for possibility—and then following that thread until it gives, one way or the other.

People love to get judgy: “A talking goat? What is this, a kid’s play?” I always counter: What about Yoda? What about E.T.? Around this time, the two-hander version I had submitted a year prior (playwriting moves at a glacial pace) won the Calicchio Prize, I asked three people on a conference call with Marin Theatre Company, “In your version of the script is there a talking goat?”

Long pause.

Then the smallest voice you ever heard: “...no?” Because why would there be? Why, in a perfectly good two-hander, would you add a talking goat? We’ve made a grave mistake. This writer has lost her mind. Fair point.

It takes a few loose marbles to conceive of something beyond the scope of one’s lived experience.

Until we see it, until it’s proven to us, we can’t quite imagine how it would work. And then, when it does, we’re left thinking either: “Why didn’t I think of that?” or “How on earth does that work so well?” But it does. Sometimes brilliantly.

For me, the trick of Weezy was to write her as nearly human. It never even occurred to me that she might be perceived as a construct of June’s imagination—that idea was presented to me years later. Others thought of her as approaching the divine.

The play’s long since been published, after the biggest NNPN Rolling World Premiere in history (ten theaters). And yet, while my dramaturg and I aren’t busy arguing over the existential quandaries of a casserole, we’re still trying to figure out who, exactly, Weezy is. The truth is—she’s defied every attempt at definition.

No one is more surprised than I am by the scope of her presence. Weezy isn’t just a goat—she’s a guardian, a shadow, a truth-teller. She lifts Alabaster out of realism and into something stranger and more expansive, turning wreckage into ritual and chaos into theatrical communion. She lets the audience in on truths the characters aren’t ready to speak, tilting the mood without ever undercutting the stakes. And as the play unfolds, it becomes clear: she’s not just narrating—she’s sentient. She shifts the frequency of a room, bends time, and moves space.

Then, as if she hasn’t gifted us enough already, when the play finally reaches its inevitable conclusion, we begin to understand that Weezy’s purpose isn’t just in service to the other characters, it’s structural. Without her sly maneuvers in Act 2, self-serving but catalytic, there would be no landslide, no watershed moment. It would read more like it did as a “rooted in realism” two-hander: a Southern Bridges of Madison County (a comparison I fully anticipated and addressed head-on).

Sidenote: That’s rule #4,924 of comedy—self-reference. If you get to it first, no one can use it against you.

Don’t sit around waiting for critics to notice the possible flaw in your argument—be the first to name it.

It’s preemptive self-awareness, and it works. In both comedy and playwriting, calling out your own quirks or unlikely devices (like, say, a talking goat) disarms the audience. It becomes part of the “bit.” Once you own it, even a self-referential motif becomes bulletproof.

Have I lost the plot? Yes, but in pursuit of my larger point. Look what unraveled from pulling one tiny thread. That’s the whole game: following instinct, listening for the goats. It’s because of Weezy’s expansiveness—her quiet, strange power—that I started calling the setting a “realm” instead of a farm. I wanted the world to feel mythic, to signal that it operates by its own rules—many of which Weezy lays out on page one.

She quickly names her ailing mother, Bib, her companion, June, and the new visitor, Alice. By the end of page 2, we know who’s who and how the card game works—we’re ready to roll. Exposition really can be that simple. Orient your audience, then get the hell out of the way.

Every play runs on its own rules—and you’re the one who sets them. Maybe pigs can fly. Maybe eggs are forbidden. Maybe the dog in the corner is Jesus Christ. Just tip your hand early so we know the score, then go for it. If audiences can follow Lord of the Rings, they can follow your stage play. I promise.

Think about the smallest character in your play. Have they said everything they need to? Consider what mischief or magic might lift your piece from the humdrum to the sublime. And most importantly, listen to the nagging voices in your head—they’re unsettled for a reason. If they were resolved, they wouldn’t be so loud. That itch you feel? That’s a loop trying to close. A thread trying to find its other end. Pay attention to what it’s pulling you toward. Every flicker of thought, every stray detail, wants to land somewhere. Maybe it goes into deep storage, maybe it gets rerouted. But in the generative process, nothing is ever truly lost—it just reshapes itself. Into landscape. Into weather. Into the goat standing quietly at the edge of the scene. Waiting.

Read an excerpt or grab your ePlay or hard copy of Alabaster at Concord Theatricals.

PAID SUBSCRIBERS GET A FREE MONTHLY STICKER!

YES, I POST SUBMISSION OPPS

https://audreycefaly.substack.com/t/submissions (bookmark this page)

PREVIOUS ARTICLES BY AUDREY CEFALY

How to Write the 10-Minute Play

This year I had the pleasure of mentoring a few dozen writers in preparation for submission to Concord Theatricals Off Off Broadway Short Play Festival. I thought I would summarize some of the advice I gave to these aspiring writers. I’d also love to hear about any techniques that work for you; feel free to comment below.

LEAN MORE ABOUT AUDREY

Visit my website for more about me and the work I do!

Audrey Cefaly's plays (Alabaster, Maytag Virgin, The Gulf, The Last Wide Open, Trouble) have garnered the Lammy Award, the Calicchio Prize, the NNPN Goldman Prize, the Edgerton, and a Pulitzer nomination. Her works have been produced at Signature Theatre, Cincinnati Playhouse, Barter Theatre, Merrimack Rep, Florida Studio, Florida Rep, Gulfshore Playhouse, and countless others. Cefaly is a Dramatist Guild Foundation "Traveling Master," an Arena Stage playwright cohort, and a recipient of the Walter E. Dakin Fellowship from the Sewanee Writers Conference. She is published by Concord Theatricals, Applause Books, Smith & Kraus and TRW.